(Reading time: 3 minutes)

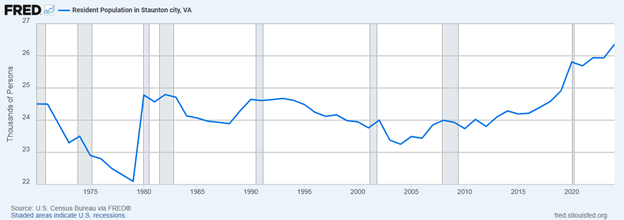

To understand how Staunton got caught with its pants down when it comes to having an adequate supply of affordable housing, it’s helpful to look at how the city’s population has fluctuated over the years. The graph above, prepared by the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, is eye-opening: from 1980 through 2024, the city’s population grew an average of 0.15% per year. Put another way, over a span of nearly half a century, Staunton’s population increased by just 6.4%.

Nothing in the world grows that slowly. Not tree trunks. Not snail shells. To put things in perspective, Virginia quadrupled its population over the same period, from 2 million to 8.81 million. The U.S. population grew by 50%.

But the reality is even more extreme than that, because as a cursory look at the chart illustrates, all of the city’s population growth has come in the past five years. After the slightest bump in 1982, to 24,796 residents, Staunton’s population began a jagged decline that didn’t regain its previous heights until 2019, when it reached 24,916. That stagnation, it’s further worth noting, occurred despite the city more than doubling in area in 1986, when it annexed 11.1 square miles from the county. By 1987, a mere year later, the city’s headcount had slipped again, to 23,933—even as it was now on the hook for providing city services to a much wider area.

So: lower population density, but more roads, water and sewer lines to build and maintain.

A key significance of these dates is that Staunton’s Comprehensive Plan, which currently is being updated and revised, was most recently adopted in July of 2019—in other words, just as population growth in the city was beginning to take off. A 20-year roadmap for how the city should grow, the Comprehensive Plan views “effective planning” as a “dynamic process” that apparently doesn’t apply to housing, because why make plans for something that isn’t dynamic? Not only was there no population pressure for more housing, but as the plan blithely asserts, “Housing is primarily a private system that is influenced by factors beyond those controlled by local government.”

So: no planning for zoning, taxation, transportation or other infrastructure changes that might promote more housing construction. Leave that to the market to sort out.

The predictable result, however, was that the stagnation in Staunton’s population growth has been pretty much matched by stagnation in new housing, even as the city’s existing housing stock continues aging. (Indeed, 43% of all housing in Staunton was built prior to 1960.) Here’s how much housing grew over the past 35 years:

Note that this is how many units of new housing of all sizes, from single-family homes to duplexes and townhomes, were permitted in the city. Despite a five-year surge in the early 2000s, presumably driven by the larger U.S. real estate bubble that ended in a recession, all but two years saw only a few dozen permits issued annually. The 35-year total was 2,790 permits—of which more than a third were issued roughly 20 years ago.

Small wonder, then, that Staunton has an inadequate housing supply, especially at the low end. And while the city has gained several new apartment buildings over the past couple of years, roughly 30% of city residents will find them unaffordable at their income levels.

Monday morning quarterbacking always sees things with greater clarity than is possible in the moment, so it’s a cheap shot to now conclude that the 2018-2040 Comprehensive Plan should have anticipated a sharp break in a decades-long trend and come up with proactive policy changes. But the Comprehensive Plan review now underway won’t be able to make that same claim, nor will a laissez-faire dismissal of the city’s role suffice to sidestep housing issues. We’ll see this spring just how much the revised plan learns from its earlier oversights and substantively addresses its shortcomings.