(Reading time: 5 minutes)

It’s only human to think that the way things are is the way they’ve always been—until they’re not. That may seem like an incongruous statement, given the extraordinarily dynamic world we’re living in. Constant social and political upheaval, as well as ever-changing rules about appropriate behavior and how we maintain relationships, can seduce us into thinking we’ve mastered this change thing—that we’ve learned how to be light on our feet as we bob and weave through everything that’s being thrown at us.

Which is true enough, as far as it goes. But learning how to respond to shifting expectations and responsibilities is not the same as learning how to effect change. Adaptation is all about reaction, not about proactively creating the world we want to see—to being able to think outside of the box, changing our circumstances to better serve our needs rather than merely responding to the world’s demands on us.

What brings all this to mind is a subject I’ve touched on in the past, albeit briefly, which is the realization that our zoning code is a decades-old strait jacket that almost invisibly shapes our built environment. Decisions that were made in the 1960s about how Staunton should be laid out, and its various land uses apportioned, have become so engrained that we rarely think about how they constrain our efforts to meet modern challenges. As a result, discussions and studies about how best to create more affordable housing, or how to make Staunton more walkable and bicycle friendly, or how to better integrate small businesses, homes and professional offices, invariably overlook root causes.

Because of this blind spot, city planners can make absurd statements about Staunton’s lack of available land for further development. The Staunton housing strategy group can meet for a year with only short mention of the zoning code, and then only to acknowledge its restrictions, without any discussion of whether those restrictions still make sense or how they can be changed to meet contemporary needs. The city’s recently adopted 11-point housing strategy mentions zoning only once, as part of an “exploration” of what might be needed to encourage additional housing options on existing properties. And it remains to be seen whether Staunton’s revision of its Comprehensive Plan will address this most fundamental issue.

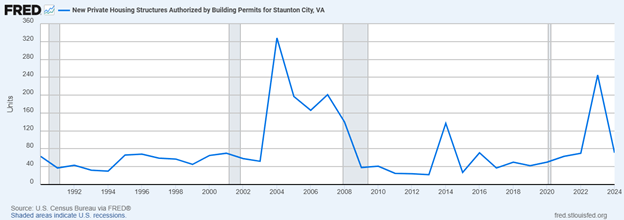

That the city’s demographics and housing needs have undergone significant changes since 1969, when the current zoning code was adopted, should go without saying. Households are significantly smaller and the population overall skews significantly older. The city itself has more than doubled in geographic size, following the 1986 annexation of 11 square miles from Augusta County—yet while both Augusta County (+76%) and Waynesboro (+35%) have seen not insignificant population increases over the past half-century, Staunton’s has inched up just 5%, and all of that over just the past decade. The amount of new housing permitted in a city with 12,352 housing units is measured most years in mere dozens (see graph above or here).

One way to describe all this is “stagnation.” Indeed, at the most recent Virginia Governor’s Housing Conference, one of the supposedly most cautionary statistics—because of its implications for future housing needs—served up by a keynote speaker was the projection that by 2050, 22% of all Americans will be senior citizens. Staunton has all but reached that mark already, at 21%—more than two decades ahead of schedule.

Older people neither want (in most cases) nor need as much house as they did when they were raising families. Smaller households—the result of more adults of all ages living alone, or with just one other person—likewise need smaller homes. And Stauntonians of all ages have emphasized repeatedly their desire to have homes within walking distance of essential shopping, as well as of cultural and recreational amenities. But none of that is possible in more than half of the city, where zoning allows only bigger homes than needed on lots that are spaced more widely apart than is conducive to walking. Moreover, that limitation means rents and home prices in the other, more desired half of the city are at more of a premium than they otherwise would be.

All this suggests that a comprehensive review of Staunton’s zoning code should be a fundamental prerequisite for any serious attempt to tackle the city’s shortage of affordable housing, but the city’s blind spot in this regard has left it spinning its wheels. Although it’s been more than five years since the state’s Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission (JLARC) directed its staff to analyze Virginia’s affordable housing needs, its conclusions have gone largely ignored locally—including the observation that “local zoning ordinances can be a substantial barrier” to “construction of new affordable housing.”

As the JLARC report also observed, “Very few localities zone more than 50 percent of their land for multifamily housing, which is the housing that is most needed in Virginia.” Although that finding is aimed primarily at the state’s more urban northern crescent, it’s worth noting that less than a fifth of Staunton’s zoned land fits that description.

Our zoning ordinances are much to blame for the fix we’re in today, but they also can ease the way out—once we recognize just how much they’re hobbling our housing market. What man has made, man can change.