(Reading time: 31 minutes)

“A slow sort of country!” said the Queen. “Now here, you see, it takes all the running you can do to keep in the same place. If you want to get somewhere else, you must run at least twice as fast as that!”—from Alice in Wonderland

AFFORDABLE HOUSING for Staunton, it might seem, is having its moment in the sun.

At least two of the current candidates for Staunton City Council have made the subject a central part of their campaign platforms. A 20-member working group has been appointed to develop a housing strategy for Staunton and, possibly, a housing commission. City leaders are exploring the ramifications of creating a community land trust as an innovative approach to building affordable housing. Two housing “summits” for the Staunton-Augusta-Waynesboro (SAW) area, last October and again in June, drew more than 170 people, attesting to a growing recognition of how serious a problem this has become. A massive housing survey of the region is being prepared by the Central Shenandoah Planning District Commission (CSPDC), holding out a promise of greater clarity about the area’s housing needs.

And all not a moment too soon.

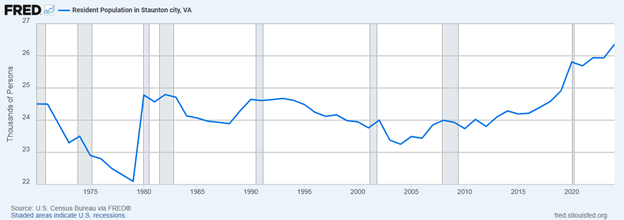

For despite the recent activity and flurry of concern about affordable housing, the region generally and Staunton specifically have been moving in reverse for many years. Consider, for example, that the most recent ALICE (Asset Limited, Income Constrained, Employed) report from the United Way, released this past May, found that only 54% of Staunton’s residents spend no more than 30% of their income on housing, widely considered as the benchmark for housing affordability. Significantly, the United Way also reported that this represents a decline from the 60% who were above that threshold in 2010. Indeed, the percentage of Staunton households that qualify as “the working poor”—people who are above the poverty threshold but whose housing costs are above the affordability benchmark—is at 34%, the highest it’s been in more than a decade

Let that sink in. This statistic means that fully a third of Stauntonians are working and trying to provide for themselves but can’t reliably afford to meet their basic needs; for many, one misstep—a car accident, a broken bone, a sick child—can mean ending up on the street for lack of any financial reserves to tide them over. (This cohort of 3,728 households is in addition to the 1,408 households that fall below the poverty threshold.) And, indeed, that’s exactly what’s been happening. As shared by Pastor Elaine Rose at a community forum last month titled, “Living on the Edge of Homelessness,” 55 evictions are on September’s court dockets for the SAW area, 15 of them in Staunton.

Not all those potential evictees will end up homeless, of course—but it’s almost certain that at least some will. And while there is a remarkable lack of reliable statistics about Staunton’s homeless population, one indicator of the problem’s pervasiveness can be found in the schools, which receive federal funds under a program called the McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act, intended to ensure all children have equal access to public education. Dr. Ryan Barber, assistant superintendent for the Waynesboro School District, told the “edge of homelessness” forum that 100 students in his city were classified as homeless at the end of the last school year. Most were living in motel rooms or were doubled up with other family members, sometimes in violation of leasing agreements; nine were in shelters, and two apparently were living in tents or cars. Now, after just two weeks of a new school year, the homeless-child count was already up to 62, which Barber said is the fastest uptick he’s ever seen.

Comparable numbers for Staunton, meanwhile, identified 58 of the district’s 2,698 students as homeless at the end of the last school year—as are 35 currently, according to Nate Collins, executive director of student services. Like Barber, he also sees “a bit of an upswing” this early in the school year.

Homelessness, of course, is just one measure of a society’s unraveling economic fabric, indicating a hopeless endpoint for those who have been unable to navigate life’s complexities. Their failure may be due to bad luck, physical or medical infirmities, psychological demons, victimization by others or any number of other causes beyond their control. But their failure is also the most visible face of a deeper social malaise, one in which a significant but largely invisible proportion of city residents routinely must triage life’s necessities—food, medical care, rent, utilities, child-care—despite working for a living.

It’s fair to ask why, in the richest country in the world and despite all the local outpouring of concern, so many thousands of our neighbors are just one step away from destitution. It’s fair to question why Staunton’s past efforts to address these problems, as well as those of the city’s neighbors, have had so little overall effect. And it’s more than fair to wonder if the current spate of concern and planning is intrinsically any different from what’s gone before, or whether it all amounts to more of the same old meaningless platitudes and ineffectual expressions of concern.

TO UNDERSTAND how we got to where we are, it’s useful to look at where we’ve been. In Staunton’s case, that means a city that historically has dealt with social issues in a fragmented fashion, sorting problems and solutions into various silos rather than viewing them all as part of one ecosystem. And when it comes to silos, some are taller or bigger than others.

The biggest silo of them all has been “economic development,” which has few natural enemies (unlike “affordable housing,” with its undertones of class warfare and government “handouts”) but which can mean different things to different people, and often is exceedingly two-dimensional. The most glaring example of this is provided by the city council’s “Vision for 2030,” which came on the heels of the Comprehensive Plan it adopted in 2019 and which unabashedly sings the praises of “one of the most beautiful places on earth.” Indeed, as it rhapsodizes from the outset, “Staunton is blessed by a palpable sense of creative energy that animates our civic life and enriches our culture,” one “manifested in a vibrant arts scene, a future-oriented business environment, and a governance philosophy that honor’s the city’s rich historical legacy while investing in an exciting future of innovation, growth and resilience.”

That future, alas, seems entirely reliant on doing everything the city can to develop the Staunton Crossing site, support local businesses, be business friendly and attract investment to its vaguely defined “opportunity zones.” The vision’s only mention of housing, on the other hand, is the claim that Staunton “has housing affordable to a full range of households.” End of story. Subject closed—except, it turns out, when the lack of affordable housing repeatedly deters the new businesses Staunton so ardently woos. With one potential employer after another expressing concern over the lack of workforce housing, it turns out that housing and economic growth are just opposite sides of a single coin.

Meanwhile, the Comprehensive Plan meant to guide Staunton in its quest to become a shining city on the hill makes its position explicitly clear, even as it proves remarkably short on actual planning. Although the “plan” devotes 22 pages to an Economy chapter, leading with the claim that its purpose “is to set goals and to establish policies which promote economic vitality” for Staunton, the 16-page chapter on Housing contends at the outset that “[h]ousing is primarily a private system that is influenced by factors beyond those controlled by local government.” What follows is a menu of census-derived enumerations of the city’s housing units, their age and market value and number of occupants per household. About the condition of those homes or how many of them meet federal standards of “decent, safe and sanitary,” there is nothing.

As to the relationship between housing and economic development, the “comprehensive” plan’s analysis boils down to just this one shockingly obvious statement: “A community’s housing policies can have significant impact on economic development efforts. Housing costs should be consistent with prevailing wages, and low levels of housing availability can diminish the ability of local businesses to retain or expand a productive work force.” Indeed.

Another indication of the city’s blinkered priorities can be seen in its organizational chart and annual budget, which relegate housing and its attendant issues to being an appendage of the economic development department. Even the library, the city’s parks and the tourist development office get higher organizational billing. The significance of this can be seen in each year’s budget proposals, which this year included the observation, “Budgets are all about choices. Staunton’s budget process begins with the submittal of each department’s budget request in December.” That’s another way of saying that how the city determines where to spend money is inherently conservative of the status quo, its choices shaped by its existing departmental structure and its needs. Without a housing department, there is no natural constituency to advance those needs.

A different window on the city’s superficial concern for affordable housing can be seen in its application for federal housing funds through the Community Development Block Grant (CDBG) program, which may be its most comprehensive assessment of the city’s housing needs. Unfortunately, the CDBG program has three potentially disparate goals—to provide decent housing, to provide suitable living environments, and to expand economic opportunities—but it’s fair to say that the first of those generally is considered primary. Given its track record to date, however, Staunton’s use of the CDBG program for decent housing has been remarkably lax.

First alerted to the possibility of tapping into this free pot of money in 2018, but apparently concluding it didn’t have the expertise to jump through the Department of Housing and Urban Development’s (HUD) hoops, the city sought consultant help by issuing a request for proposals (RFP) on March 22, 2019. The RFP provided only a two-week window in which to respond, so perhaps it wasn’t surprising that it resulted in only one bid, from Mullin & Lonergan Associates, which is headquartered in Pennsylvania but has several Virginia contracts. What is surprising is the city council’s willingness to accept a non-competitive bid to manage more than $1.6 million on its behalf, as it readily agreed to a two-year contract that paid M&L Associates 20% of the grant money it would receive—the maximum overhead payout allowed by HUD. Two years later, Staunton and M&L further agreed to two, 2-year renewals of the same deal.

Here’s what Staunton got in exchange for paying M&L to administer its grant money:

- For the federal fiscal year ending Sept. 30, 2020, it received $354,433 in CDBG funds, of which it expended just $97,654. Expenditures included $70,887 for “general administrative and planning,” all or almost all of which went to M&L Associates. The balance spent provided 719 meals on wheels, 840 one-way rides for 37 social services clients, security deposits or first-month’s rent for 12 formerly homeless people moving into housing, and advocacy services for 29 youths.

- For the fiscal year ending September 30, 2021, the city received $352,830 in CDBG funds, of which it expended $112,875; $49,642 of that was assigned to general administrative and planning. M&L Associates reported that work had begun on a project for new sidewalks on a significant stretch of West Beverley Street, as well as building infrastructure for the “A Street Aging in Place” project, which is intended eventually to provide 25 new affordable housing units. (The Beverley Street project is in limbo as of March of this year, when the city failed to get any bids to actually do the work.) CDBG funds also were used to replace roofs on two homes and to provide 120 meals on wheels, 252 one-way rides to 29 clients, 10 security deposits for homeless people transitioning into rental housing and advocacy services for 48 youths.

- Fiscal year ending September 30, 2022, the city got $344,362 in funding and spent $133,249, of which only $29,811 went to planning overhead. There is no mention of the Beverley Street sidewalk project progressing, and only 4 new roofs were installed, against a projected five-year total of 50. “Identifying contractors has been a challenge, and the costs of materials have impacted the program,” M&L Associates explained, adding, “Homeowners are still reluctant to have contractors at the home due to the pandemic.” There is no record that anyone questioned this assertion. Meanwhile, site prep for the A Street project continued, and 230 Staunton residents received social services, including 17 free legal help, 122 meals on wheels, 37 free rides, 46 youth advocacy and 7 rent deposits.

- For the fiscal year ending last September, 2023, Staunton received $317,340 in CDBG funds and, for the first time, spent all it was given—and then some, finally drawing down a bit of the $707,848 in its unspent balance. Money was spent on completing a waterline on Rockaway Street that serves 26 homes and 14 multifamily units, as well as on upgrading the Salvation Army’s soup kitchen and service delivery area. Another 6 homes got new roofs, bringing the grand total to 12. Services were provided to 112 people, with meals on wheels continuing a downward trend to just 103 people served, 27 people getting fee rides, 12 getting legal services, 36 youths receiving advocacy help, and only 6 homeless people helped with rental security deposits. Oh—and $65,185 was expended on general administration and planning.

For those keeping track, all this adds up to $1.37 million dollars received by Staunton over the first four years of a five-year program, of which roughly half ($675,031) was not spent in the program years it was awarded. And of the money that was expended, nearly a third ($215,524) went to overhead, which essentially means M&L Associates. Other big chunks went to water and sewer projects ($150,642) and to the Salvation Army ($55,000), while most of the rest went to various client services, which HUD caps at 15% of its grants—a cap the city apparently is bumping up against, if it hasn’t already exceeded it. Money spent on actual housing? Not so much.

There are, to be sure, numerous reasons for this sad history, not least a pandemic that derailed all of society, and its effects on Staunton should not be discounted. But nor should the pandemic become an all-encompassing excuse for sloppy oversight by an outside contractor that nevertheless ensured its own financial needs were met, or a city administration and political leadership that never seriously questioned the work that was done on its behalf.

That’s not to say the money was spent outside of HUD guidelines, and we have yet to see what the program accomplished in this, its fifth year, which we won’t know for another two to three months. Moreover, the people who got hot meals or free rides and legal services undoubtedly were grateful for the help. But the opportunity to use a big pot of money to make lasting affordable housing improvements has been largely squandered, and thus far there’s no sign that anything is going to change any time soon, as M&L Associates is continuing its relationship with Staunton and recently finished preparing the next five-year CDBG spending plan.

In summary, then, one might reasonably question Staunton’s diligence in tackling its affordable housing problem to date.

WHY HAS THE city been so inept at dealing with this situation?

Part of the reason, as already argued, was a failure to recognize that the city had a problem in the first place—of all the aspects of city life described in various city documents, housing historically has been all but invisible. Nor has the city, until relatively recently, considered that it has a role to play in ensuring there is adequate housing for the people working in its stores and industrial plants, playing in its parks and attending its schools. It’s hard to fix something if you don’t first acknowledge that it’s broken, and it’s hard to fix something when you do recognize a problem but don’t have an appropriate response mechanism.

But even without those limitations, having accurate, reliable information on which to base solutions is critical—and when it comes to housing, that information is absolutely rife with bad data and outdated statistics. Moreover, the gatekeepers overseeing this information swamp are either oblivious to its inconsistencies or too lazy to care.

Not to pick on M&L Associates, but consider the work it put into the two Consolidated Plans it has prepared thus far. The 2019 plan relied on information about populations, housing stock, income levels and other variables that predated the plan by several years—and the 2024 plan persists in using a substantial number of statistics from 2017 or earlier, even when more recent data is available, as for example from the 2020 U.S. census. That means its findings have completely missed this decade’s explosion in real estate prices, rise in unemployment and other pandemic and post-pandemic economic trends. Moreover, because it used a cut-and-paste approach in assembling Staunton’s second five-year plan, uncritically lifting large blocks of copy from the first plan it had prepared, M&L Associates overlooked some critically important developments, such as Virginia’s increase in the minimum wage. That meant less work for M&L, to be sure, even as it continued raking in its 20% fees, but it also seriously skewed its subsequent calculations of housing affordability

To its credit, M&L Associates corrected the mistake when it was pointed out—but only in the passage called to its attention. The original, misleading assumption that the minimum wage remains at $7.25 an hour—in Virginia it’s now $12—persists elsewhere, including in a so-called “analysis.” Then again, the 2019 consolidated plan also included some howlers that were never intercepted, such as the statement that “there were 9,260 persons with disabilities in Staunton in 2015, representing 16.7% of the population”—which, if true, would more than double Staunton’s total headcount, to 55,449. Or take the plan’s statement that “9,676 housing units in the City of Staunton are at risk of flood hazards (approximately 2% of the housing stock)”—which would credit Staunton with 483,000 homes, comparable to Spokane or Boise.

Such casual pronouncements have a way of getting picked up and repeated uncritically by others, muddying the data pool. Garbage in, garbage out. They also attest to the problem of reporting from a distance by people who don’t have hands-on proximity to a situation, raising the question of why so much money is being spent on an outside consultant with a tendency toward phoning it in. That very question was raised by Staunton’s housing planner and grants coordinator, Vincent Mani, in a Sept. 23, 2022 memo to the city’s director of community and economic development, just a month after he was hired. The memo detailed Mani’s frustrations with dispersing CDBG funds that he attributed to administrative errors by M&L Associates, which he might have been able to defend, had he not also gone on to accuse the community development department of “acting like a hostage” to consultants who viewed the city as “a cash cow.” That didn’t go well. A little more than three months later, Mani was out of a job, and no one has held M&L’s feet to the fire since.

But the problem isn’t just one sloppy consultant. Meaningful numbers are hard to come by because most of the housing statistics everyone uses are drawn from U.S. Census Bureau data, and those statistics aren’t granular enough to zero in on specific properties—at best, they describe housing conditions across a census tract in order to protect personal privacy. So, for example, planners can tell you how many homes in an area are overcrowded or have inadequate bathroom or kitchen facilities, but they can’t tell you which homes those are. That makes targeting relief to those who need it the most problematic, at best, and so funds get funneled (if they get funneled at all) to more easily observable problems, such as which roofs need replacing.

The numbers game also ends up producing some wildly disparate pictures of the housing market. The recent SAW Housing Summit, for example, was informed that there are 2,184 “long-term vacancies” in the Central Shenandoah region, which is another way of describing houses that are sitting empty and in some cases abandoned, falling even further into disrepair. But the CSPDC Housing Program Report 2023-24, released in late August, reported that the region has 115,000 households and 130,000 housing units—or 15,000 housing units more than the number needed. How to account for that discrepancy?

The CSPDC’ s new head planner, Jeremy Crute, contends that a “healthy” housing market will have a 5%-8% vacancy rate, meaning homes that are empty but not abandoned. Yet even an 8% vacancy rate brings us to only two-thirds of the 15,000 gap, and in any case, the area’s housing market is “among the tightest” in the country, with a median time of just six days for homes to stay on the market, compared to the 30- to 60-day supply in a “healthy” housing market. Staunton’s rental market, meanwhile, has a 1.1% vacancy rate.

Knowing which numbers to trust is essential to formulating sound housing policy. In this case, perhaps 2,000 of those 15,000 excess housing units might benefit from rehabbing—but of the balance, how many are second homes? How many are being used as investment properties, as short-term vacation rentals, like Airbnbs, or just being left empty for a year or two before being flipped? Are those possibilities something that city leaders should investigate and perhaps seek to control, as other communities across the country are doing, to preserve affordable housing for local teachers, cops, firefighters and other essential workers to live in?

The tight supply of homes for sale, a problem not unique to Staunton, is made worse for many potential buyers by a wealthier class of all-cash buyers, who squeeze out lower-income households who need to secure financing before they can buy. But that squeeze also puts more pressure on the rental market, which is in equally short supply. This results in rents being higher than they would be in a less constrained market, and also has a long-term add-on effect of contributing to the deterioration of borderline properties, as landlords have less incentive to spend on maintenance and repairs.

Keeping in mind the unreliability of housing statistics, it’s nevertheless suggestive that the SAW housing summit also reported a mismatch between household size and housing stock, much of which was built decades ago for significantly larger families than is true today. So, for example, 81% of Staunton households today have three or fewer family members, whereas only 30% of housing units have two or fewer bedrooms, underscoring a need for additional smaller (and presumably less expensive) housing units to accommodate smaller households.

Other clues about the dangers facing the city’s housing stock are reflected in the 2022 American Community Survey, one of the few exceptions to the otherwise outdated statistics compiled by the city. According to the survey, 4,096 households in Staunton—or roughly 40% of the total—consist of a single person living alone; of those, 21.5% have incomes below the poverty level, a rate nearly double the city’s overall 11.4% poverty rate. One can only imagine the condition of many of these homes, since there is no hard information, but the following survey comment is suggestive: “Repeatedly during the public outreach process, the poor condition of existing housing stock was also [i.e. in addition to its cost] identified as a concern, particularly among the elderly who lack the financial resources to maintain their property.”

In other words, Staunton is experiencing a silent downward spiral of a population at growing risk of homelessness, largely hidden within a Potemkin Village of disintegrating homes. As one decays, so does the other—with ominous consequences for the city at large. Intervening with this population therefore should be seen not just as a compassionate response to human fragility, but as a self-interested move by the city to prevent the proliferation of slums and to present an attractive, vibrant housing market to the economic interests it’s trying to attract.

WHAT IS THE CITY doing in response to all this? And what can it do that it isn’t currently doing?

To the first question, the bleak answer is: “not nearly enough.” Perhaps because of the “hands-off” attitude enshrined in the Comprehensive Plan, in which housing was seen as something best left to the private sector, city staffing for housing needs has been minimal, as has its allocation of resources. No surprise, then, that the backlog of issues keeps growing.

For example, the city’s version of public housing, the Staunton Redevelopment and Housing Authority, currently owns 150 housing units for low-income tenants and administers an additional 248 Section 8 housing vouchers, for a theoretical total of 398 low-income households served. But only 214 Section 8 vouchers were actually being used as of this past May, apparently because HUD’s increases in the Section 8 voucher budget have not kept pace with rising market rents. Less federal money means the authority’s resources “are insufficient to meet the local need,” which in plain English means there were 1,337 families on the Section 8 waiting list as of May, plus an additional 325 families on the public housing list. Even more of a shortfall is expected after Oct. 1, when the next federal fiscal year begins.

Meanwhile, an unspecified “some” of the authority’s units will need renovations in the “near future,” including replacement of HVAC units that are 12 to 13 years old, sidewalk repairs, and roof repairs or replacement.

When it comes to underwriting large capital improvement projects, the city has a highly conservative approach that hews to a mostly “pay as you go” philosophy that relies on special funds. Some of these funds have dedicated, user-funded income streams—e.g. stormwater improvements—but others rely on annual transfers from the general fund that often don’t keep pace with rising prices. This latter approach currently is funding three capital improvement reserves, at $287,261 per project per year, only one of which—the Uniontown Neighborhood Improvements Reserve—explicitly contemplates renovating existing houses, as well as building up to 40 new single-family homes, presumably by private developers. Or that’s the “plan.”

A second capital improvement fund, the West End Revitalization Reserve, might appear at first glance to be a natural for addressing similar housing improvements, especially in census tract 2, which has a median household income of just $35,000—two-thirds that of Staunton overall—and a median home value roughly 75% of the city-wide median. Yet the revitalization plan, at least thus far, is more fixated on improving roads and sidewalks and on attracting retail and commercial development than on fixing up houses or building new ones.

Meanwhile, the mismatch between reserved funds vs. the anticipated costs of Uniontown redevelopment can make one think this is little more than a cynical exercise in placating neighborhood activists. The plan’s own calculations estimate that providing necessary water and sewer extensions to the area—a prerequisite for home construction—will cost more than $5 million, while necessary road improvements and construction of a pedestrian/bicycle bridge over the railroad tracks that split Uniontown in half will cost many millions more. The five-year reserve, meanwhile, is projected to accumulate just $1,436,305 over that time, with no explanation of how the shortfall will be made up.

And while one might expect the community development budget, because of that department’s proclaimed attention to “housing and quality of life needs,” to include at least some resources for affordable housing, that doesn’t appear to be the case, apart from some planning functions. By comparison, the city’s annual allocation to the tourism office is more than double the Uniontown annual reserve set-aside, and departmental spending just on advertising is $232,000 a year. That’s not to say such money isn’t well spent, but simply to observe that how it’s spent underscores Staunton’s actual priorities. Housing is not on that list.

Against that backdrop, the city council seems to be pinning its hopes on shaking things up with a “housing strategy” prepared by its relatively new housing planner and grants coordinator, Rebecca Joyce, who was hired in May last year to replace Vincent Mani. More than a year later, that initiative may finally be getting off the ground, with the naming of a 20-member working group tasked with developing “an action plan for implementing housing policy objectives,” including the possible creation of a housing commission. An uncharitable description of this effort would be to call it “planning for more planning,” but given the overly large size of the “working group,” its composition—heavily weighted with the same non-profit housing advocates that have been kicking these issues around for years—and its lightweight schedule of a mere four two-hour meetings over the next eight months, that description may be all too apt.

Further handicapping this effort is the city’s lack of accurate and timely data, as already described above, especially when it comes to describing housing inventory. The massive housing study that the CSPDC has been promising since late spring, initially projected to be available in July, then August, and now by late September, was intended to provide much of the working group’s jumping-off point, although as already mentioned, it likely will not have enough detailed information to be as useful as needed. Indeed, the repeated delays in releasing the study suggest it is an unwieldy data dump, hobbling not just the city’s planning but the next SAW Housing Summit meeting, scheduled for Sept. 4, which has reconfigured its format to have just two working groups instead of the four that were originally planned.

It doesn’t have to be this way. The City of Lexington, for example, applied early this year for a $50,000 CDBG planning grant to conduct what is commonly described as a “windshield survey” of all city housing. The grant was awarded in March, an RFP was published in April, and after receiving four bids, Lexington awarded a contract to Summit Design and Engineering. The expectation now is that the street-level survey will be completed by March—or just about the time Staunton’s housing working group will be holding the fourth of its meetings—and will give Lexington officials the kind of detail they need to assess their housing stock and determine how best to upgrade it.

Would that Staunton were in a similar position!

ONE WAY that affordable housing advocates have been consoling each other is by citing the starfish parable—the one in which a young boy is walking along the beach and tossing stranded starfish back into the ocean, one by one. His companion, on seeing how many thousands of starfish nevertheless won’t be saved and are doomed to die, points this out to the boy and observes that his efforts won’t make any difference in the larger scale of things. “To this one it will,” the boy replies, heaving yet another starfish into the sea.

For those advocates, whether from the Shenandoah Valley Partnership, Habitat for Humanity, Valley Mission, Valley Community Services Board, Valley Supportive Housing, Renewing Homes for Greater Augusta, and many faith-based organizations, the difference they make is in the individual lives they touch, and that work should be acknowledged and honored. But at the same time, starfish analogies should not suffice for elected officials and policy makers, whose ambition should be to make such individual interventions unnecessary, or at the very least unusual.

Staunton’s affordable housing issue is a systemic problem, and lasting remedies have to be systemic in nature. For that to happen, however, the city must acknowledge its conflicted history of dealing with housing issues—or its hypocrisy in acknowledging it has a problem, but then failing to address it in any meaningful way. For example, the committee that is currently rewriting the Staunton Comprehensive Plan should acknowledge that the existing plan’s contention that housing problems are beyond the reach of local government is a cop-out. And in making that acknowledgment, the committee should do what the existing “plan” so widely fails to do . . . which is to plan.

The second missing piece in the city’s response is its lack of an accurate and actionable database. The regional housing study that CSPDC is preparing was viewed by some as providing that information, but it’s become clear that it will be too broad and non-specific for Staunton’s needs, and in any case probably won’t be ready for the housing working group’s first meeting, planned for later this month. That meeting was planned to provide working group members with a “housing data review and regional housing study,” but the working group’s time might be better spent discussing how it might apply for the same kind of CDBG grant that Lexington landed.

The third and truly critical reason why Staunton keeps spinning its wheels on the housing issue is its lack of a centralized overseer for its housing needs, leaving those needs—and the people who have them—at a severe disadvantage when it comes to budgeting and policymaking. There is no champion for affordable housing when the city’s spending plans are being formulated—unlike, say, for the library or city parks. The current “housing strategy” initiative, with its bloated working group and stingy meeting schedule, may result in creation of a housing “commission,” which may be a good start. But such a protracted process is overly complex and not reflective of the urgency of the problem that’s being addressed: it would be enough to reshuffle the city’s organizational structure to create a new housing department, with its own director, its own staff and its own budget line, and it wouldn’t take a year or more to do so.

With those three prerequisites in place, Staunton might finally put an end to its scattershot response to housing issues and the people who are battered by them. The things the city does to deal with homelessness and the lack of affordable housing are not just insufficient, but also fragmented and uncoordinated, a pastiche of band-aid remedies with little relationship to each other. There is no context, no comprehensive plan, despite all the documents that display that noun on their title pages. And because there’s no overall plan, no overall direction and only limited data, there’s also no readily available way of determining whether progress is being made, or whether things are moving in reverse. The ALICE report referenced at the beginning of this white paper indicates, alas, that it’s the latter.