(Reading time: 13 minutes)

The calendar may insist that winter won’t arrive for another six weeks or so, but anyone who ventured outside Tuesday morning knew otherwise—not when the temperature hit a bone-chilling 24 degrees Fahrenheit. Tuesday was a good day, in other words, to be bundled up in a cozy bed or snuggled with a good book under a comforter in an easy chair. If you were that lucky.

It’s ironic, then, that just 12 hours earlier the city had held the third of three public workshops addressing proposed revisions to its comprehensive plan. Dozens of goals and draft strategies were outlined on multiple easels for Staunton residents to ponder and evaluate, spanning everything from land use, housing and economic development to transportation, public infrastructure and education. A section on health and human services stressed “active living, healthy food access and a clean environment.” Public safety, environmental resources, art and recreation all received due consideration.

But nowhere in all this planning and verbiage was there any mention of Staunton’s homeless population, or its needs and how those needs might be met. True, the section on housing gave a vague nod to promoting “affordable housing options for people of all incomes, needs and abilities,” but it remained silent regarding those unable to take advantage of such promotions. Nor did the draft comprehensive plan set a goal of eliminating homelessness by any particular date, and at no point did it acknowledge, much less prescribe, the kinds of services a homeless population requires. As far as the comprehensive plan is concerned, Staunton residents without permanent shelter simply don’t exist.

Winter’s advent will make that fiction harder to maintain.

Let’s take stock. A long-promised day shelter, offering homeless people refuge from extreme weather, remains as elusive as ever, in part because of a crumbling commitment by First Presbyterian Church to allow the use of its premises, but also because of a lack of financial and leadership backing from city council. Meanwhile, the Waynesboro Area Refuge Ministry (WARM), which was to operate the day shelter and which already provides emergency overnight shelters from late November through March, just published its schedule of participating churches for the upcoming season. Two of the week-long slots remain unfilled, at an exceptionally late date in the planning cycle, and there are reports that a third also may fall vacant because one of the congregations got cold feet and is backing out. Meanwhile, eight of the 18 overflow slots, for when the primary host churches receive more than 40 people, likewise remain unclaimed.

The Valley Mission, the area’s transitional shelter for homeless people working on reentry into the workforce and established housing, has 89 residents and is at full capacity—as it has been for several years—and is as far as ever from meeting its goal of a six-month turnover. “Yes, the average length of stay has been much longer than a year,” concedes director Sue Richardson. “In fact, we had two different women who were here four years each,” which puts a whole new meaning on “transitional.”

Then there’s Valley Supportive Housing, which provides affordable housing for clients diagnosed with mental illness, intellectual disabilities or addiction—people, in other words, who otherwise would be prime candidates for living on the streets. It also is at capacity, with 68 tenants, and has a waiting list of 43—the biggest it has been in at least a decade. “Two years ago it would have been half of that,” says director Lou Siegel, who says some of those on the waiting list are at Valley Mission, some are in temporary accommodations with family members, and some are living in their cars.

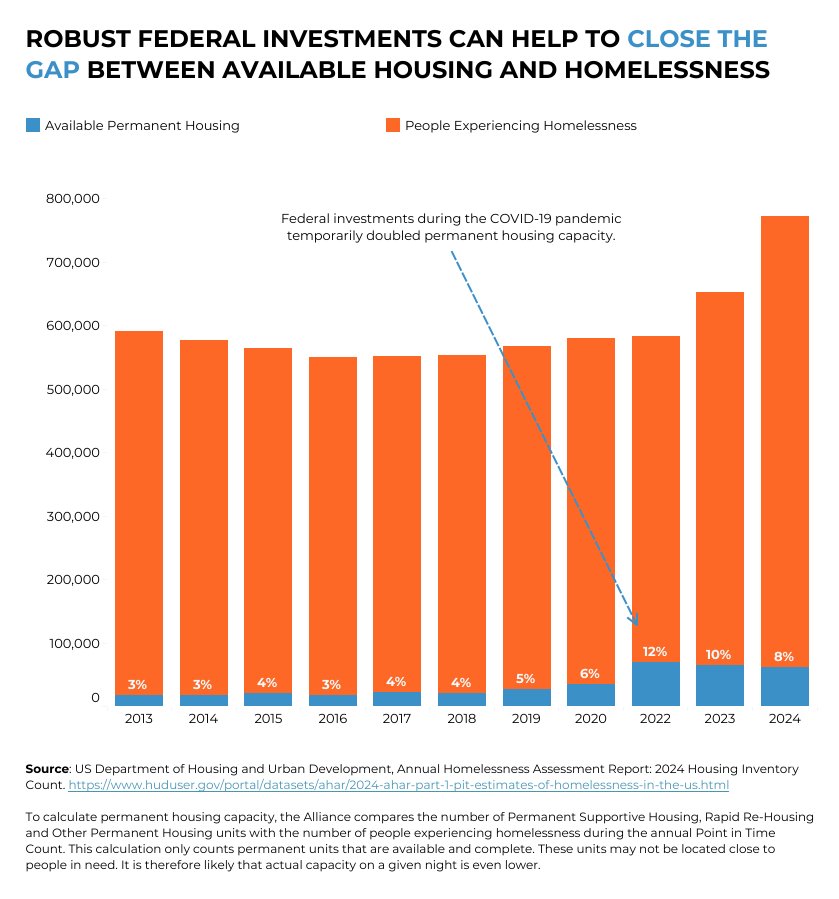

Both Valley Mission and Valley Supportive Housing are in a perpetual scramble for adequate financial backing, which comes in bits and drabs from local sources such as the city’s Community Development Block Grant (CDBG), the Community Fund and the Community Action Partnership of Staunton, Augusta and Waynesboro (CAPSAW). CDBG is all federal money, while CAPSAW receives nearly half of its funding from the federal government—which means both revenue streams are threatened by the current political climate.

Meanwhile, the area’s homeless population, while always difficult to assess accurately, is almost certainly not diminishing. WARM director Alec Gunn estimated this summer that the SAW region has 250 homeless people. And while this year’s Point in Time (PIT) count—a one-night snapshot—found fewer unsheltered homeless people than last year, bitterly cold weather the night of the census may have driven them deeper underground. Moreover, as a surprised Lydia Campbell of the Valley Homeless Connection observed, of the 157 sheltered and unsheltered people who were counted by the 2025 PIT census, 71 reported they were homeless for the first time, up from 51 in 2024.

All of which is to say, the Staunton Comprehensive Plan as it’s currently coming together has a gaping hole big enough to push a shopping cart through.

FAILING TO SEE THE CITY’S HOMELESS population means the comprehensive planners also fail to ask why the homeless exist in the first place. If you don’t see a problem, you can’t solve it.

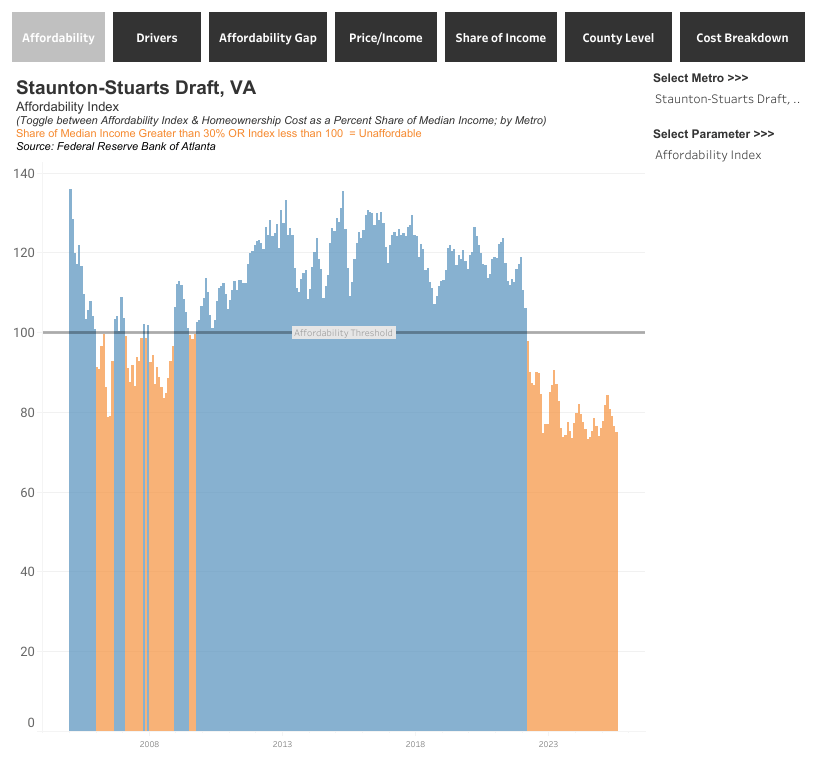

Homelessness, with some rare exceptions, is a signal that the system itself is failing. At its most basic doh! level, homelessness results from an inadequate supply of housing that people can afford. With rental vacancies at or around 2% and housing costs far outstripping the affordability provided by median incomes, the inevitable outcome has been compared to a game of musical chairs, in which the number of available chairs is always less than the number of people circling them. When the music stops, someone always ends up on the floor.

The obvious question: why is that? Why, in a market economy, isn’t more affordable housing being built? The law of supply and demand suggests that when demand exceeds supply, market forces will step up production until the imbalance is corrected. You want to end homelessness? Simple: build more housing at a price that people can afford. So . . . why isn’t that happening in Staunton?

The Staunton Housing Strategy Group spent a year purportedly wrestling with this very issue, ultimately producing this past summer what it optimistically called “Staunton’s Pathway to Affordable Housing and Housing for Working Families.” Yet it’s notable that of the 19 members of the workgroup, only one, Stu Armstrong, could be categorized as a builder or developer—that is, as someone from the supply side of the supply-demand equation. And Armstrong, as it turned out, didn’t attend a single one of the group’s four meetings.

What that left was an assortment of political leaders, planners and heads of non-profit social agencies holding a one-sided conversation about how best to plug the city’s housing deficits. The result was a set of 11 strategies that, while not entirely without merit, only tangentially address the critical question of how to increase the city’s stock of affordable housing, and do so on a less than urgent timetable. For example, completion of a “strategy” to allow accessory dwelling units (ADUs) in the city is expected to take 18 months, a process that won’t add any new homes but will create the possibility of some down the road.

Foot-dragging over ADUs, which have been given the go-ahead in many municipalities in Virginia and other states, is emblematic of a more fundamental problem that the housing strategy group didn’t address: the city’s zoning code. The main reason Staunton doesn’t have tiny homes or converted garages that can provide additional housing on established home lots is that its rules don’t allow it. Allowing ADUs therefore requires yet another amendment to the zoning code—the default response to every fresh demand for land use, such as creating exceptions to minimum lot size in Uniontown. And just like computer operating systems that over many years become an unwieldy morass of work-arounds, patches and buggy over-writes, zoning codes tend toward increased complexity with every change. What the city’s “pathway to affordable housing” proposes is more tinkering with the underlying code. What the city needs is a new operating system.

It’s not just ADUs that are at issue. Ask developers—as the housing strategy group did not—why they’re not building more affordable homes in Staunton, and the answer you’ll get is a) that the permitting process is too onerous, and b) that they can’t afford to do so. Answer b) to some extent is a consequence of a), because it costs money and time (which is money) to comply with zoning and permitting regulations. But the bigger reason is the zoning itself, which not only limits how a specific piece of land can be used, but which arbitrarily dictates so many other construction variables that the only homes that pencil-out for a builder are expensive ones.

Zoning codes, as the name suggests, create “zones”—a zone for housing, a zone for shopping, a zone for manufacturing, and so on. That made sense when used to keep foundries or slaughterhouses away from residential areas, but it also created artificial divides that segregated functions—stores, homes, offices, apartment buildings, schools, cultural centers—that were all mixed together before zoning codes were created. That mixture, still found and now treasured in downtown Staunton, created a lively, walkable and rich urban environment. The imposition of zones, on the other hand, created land-use monocultures—predominantly large areas of all homes, but also of all mercantile and other activities, as in shopping centers and office parks—that then necessitated a car culture for most people to get to work, do their shopping and go to church or school.

It should be noted that there is nothing intuitively logical about a zoning code’s specific requirements. Staunton’s R-1 residential zoning, for example, is distinguished from R-2 zoning primarily by its minimum lot size, of 15,000 square feet versus 8,750 square feet. But the R-1 lot also must have a minimum lot width of 75 feet at the front and any home built on it must have a minimum 30-foot front set-back, a rear yard at least 35 feet deep and maximum lot coverage of 30%. The same requirements for R-2 homes, meanwhile, are a 70-foot minimum lot width, a 25-foot front setback, a rear yard at least 30 feet deep and maximum lot coverage of, yes, 30%. Why? Why a 25-foot setback for one but a 30-foot setback for the other, or a lot width of at least 70 feet for R-2 but an extra five feet for R-1? What compelling urban mathematics produced these arbitrary requirements?

For builders and developers looking at a lot of 45,000 square feet (just a bit over an acre) zoned R-1, the maximum they can build is three homes. They can’t build cottage courts, fourplexes, townhomes or any number of other configurations increasingly known as “missing middle” housing—housing more dense than single-family homes but smaller than apartment buildings. Instead of 10 or 12 homes they can build just three, so those three are going to be built at a level where they can fetch top dollar, not at a density that would allow at least some affordable homes to be part of the mix. And in Staunton, the great majority of land is zoned R-1 or R-2, leaving scant room for more modest dwellings.

Zoning’s arbitrary guidelines do preserve a uniformity of appearance that appeals to some people, but which others find stultifying—or as summarized by city planning critic Jane Jacobs, more like taxidermy. Yet their very persistence creates an aura of inevitability, as if the only (unthinkable) alternative is anarchy. And so, even as local feedback to Staunton’s comprehensive plan repeatedly stresses walkability, community, and an integration of work, play and housing, the main obstacle to realizing that vision has gone largely untouched. Despite a proposal to reduce the total number of zoning sub-categories, the comprehensive plan promises to preserve the overall zoning approach. The builders’ dilemma will go unaddressed.

WITHOUT A SERIOUS EVALUATION of how zoning got us into the housing crunch we’re now struggling to overcome, there seems little hope for improvement.

Defenders of the status quo will point to the equivalent of a techie’s work-arounds and system upgrades, including district overlays, special use permits and other ways to game the system while leaving the underlying code untouched. But there’s a reason DOS-based systems have been left behind, not least because they became too expensive to maintain in terms of talent and manpower.

Nor does junking zoning codes mean descending into anarchy. Just as DOS-based systems were replaced by GUI ones—the graphical user interfaces we use without a second thought because they’re so intuitive and user-friendly—so traditional zoning codes are giving way elsewhere to form-based zoning. Traditional zoning codes are a top-down approach that segregates land uses. Form-based zoning is less concerned with regulating land use and instead prioritizes the physical form, scale and character of buildings and public spaces. Because form-based zoning is a bottom-up approach that regulates how buildings interact with the street and with each other but not what use they’re put to, they tend to encourage infill and the development of walkable, mixed-use neighborhoods and high-quality public spaces.

That doesn’t mean truly disruptive or dangerous industries or businesses can’t be relegated to specific buffered areas, but the landscape is otherwise opened up to a free market constrained primarily by the same kind of rules that apply to coloring books: use whatever color you want but stay within the lines. Observe the regulations we’ve adopted about building height, scale, massing and relationship to the street, but otherwise put your land to the most productive use you can envision.

That may sound radical at first blush, but it is in fact what occurred in what are now the most treasured parts of Staunton—before the zoning code was adopted. It’s also what a growing number of municipalities around the country are adopting, from Mesa, Arizona to Cincinnati, Ohio to parts of Gaithersburg, Maryland. Form-based zoning deserves, at the very least, a serious examination and consideration by those who are revising a comprehensive plan for Staunton that has a 20-year outlook.

Here’s the bottom line: developers aren’t building affordable housing because our zoning code makes it prohibitively expensive to do so. The real-world consequences of sticking with that creaky form of land-use regulation are, quite predictably, more people without homes. And because as a society we apparently have neither the money nor the political will to minister to those people’s most basic needs, every homeless person we see on the streets, huddled in doorways, or sleeping in uninsulated tents or cars, should be a reminder that we’re not addressing root causes of a social disease.

The Staunton Housing Strategy Group failed to do so. The comprehensive plan’s designers are likewise missing the mark. Who’s left?